Stover Lecture Series

The Stover Lecture Series is named for professor of history John F. Stover, who taught at Purdue from 1947 to 1978. Stover was a leading scholar of American history with a specialization in the history of American railroads. After his death in 2007, Stover’s wife Marjorie and children Charry and John established an endowment used for the benefit of a lecture series on issues of significance and relevance to the Department of History. The series presented its inaugural lecture in 2009.

In past years, our John F. Stover lecturers have presented talks on Civil War America as depicted in literature and movies, WWII-era France and race relations with U.S. African-Americans, early 20th century Japan Nobel laureates in the U.S., pre- and post- invasion Iraq, Mexican immigration laws of the late 1800’s to the present, and the role of jazz in the liberation of African-Americans and combating prejudice.

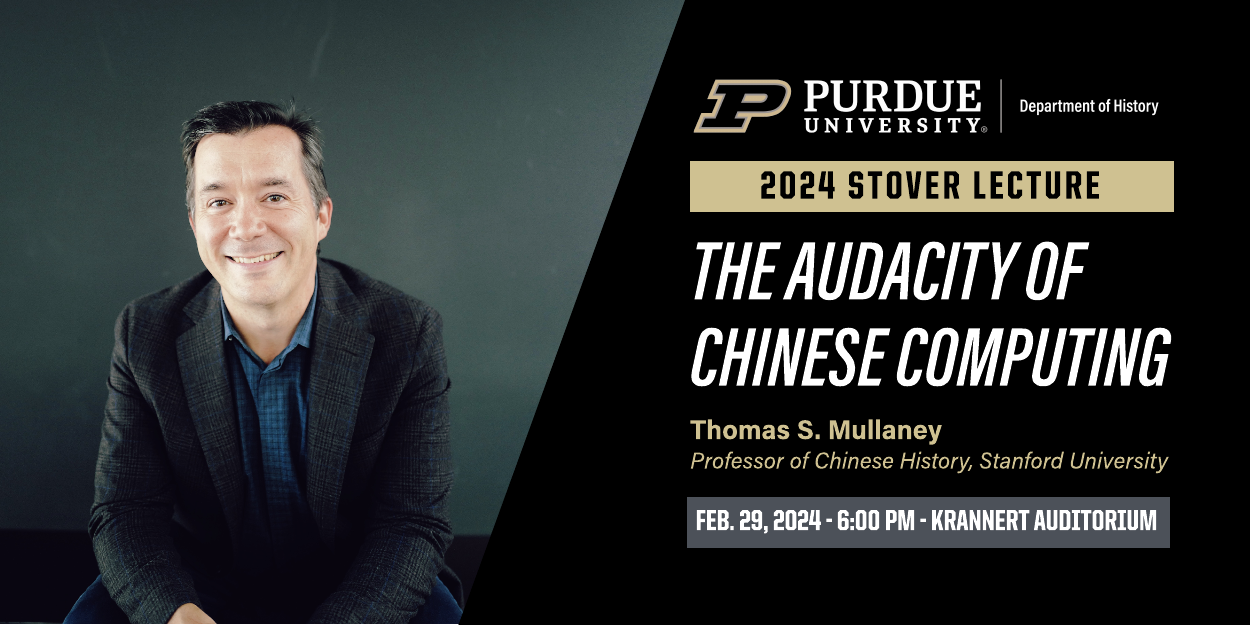

2024 STOVER LECTURE

In 1989, a Chinese engineer made an audacious prediction: within his lifetime, Chinese would surpass English as the fastest computational language in the world, where "with leisurely keystrokes, users will be able to reach or greatly outpace the speed of human speech." Outlandish as this prognostication was, it has largely come true, with the fastest Chinese inputters reaching mind-boggling speeds of 221.9 characters per minute—or 3.7 Chinese characters every second.

How is this possible? For a person living between the years 1850 and 1950—the period examined in Stanford professor Thomas S. Mullaney’s award-winning book, The Chinese Typewriter—the idea of producing Chinese by mechanical means at a rate of over two hundred characters per minute would have been virtually unimaginable. Within Chinese telegraphy, dating back to the 1870s, operators maxed out at perhaps a few dozen characters per minute. In the heyday of mechanical Chinese typewriting, from the 1920s to the 1970s, the fastest speeds on record were just shy of eighty characters per minute (with the majority of typists operating at far slower rates). In the dawn of the modern Information Age, that is, Chinese was consistently one of the slowest writing systems in the world.

What changed? How did a script so long disparaged as cumbersome and helplessly complex suddenly rival—exceed, even—computational typing speeds clocked in other parts of the world? Previewing his new book, The Chinese Computer: A Global History of the Information Age (forthcoming in May 2024), Mullaney charts out the history of computing in China, a terrain that remains unmapped despite China’s present-day status as a global IT powerhouse.

Thomas S. Mullaney is Professor of Chinese History at Stanford University, a Guggenheim Fellow, and the recipient of Stanford’s highest award for excellence in teaching, the Gores Award. He is the author or lead editor of 8 books, including the forthcoming The Chinese Computer: A Global History of the Information Age; Where Research Begins: Choosing a Research Project that Matters to You (and the World) (University of Chicago Press, 2022, with Christopher Rea); and The Chinese Typewriter: A History (MIT Press, 2018) (winner of the John K. Fairbank prize). His writings have appeared in Fast Company, MIT Technology Review, Quartz, the South China Morning Post, Tech Crunch, the Journal of Asian Studies, Technology & Culture, Foreign Affairs, and Foreign Policy. His work has been featured in Radio Lab, The Atlantic, the BBC, and in invited lectures at Google, Microsoft, Adobe, and more. He earned his BA and MA from the Johns Hopkins University, and his PhD from Columbia University.