Archaeology by drone

Multidisciplinary team from Purdue helps conduct innovative research on Mediterranean island

Imagine you are an archaeologist studying an island that has been uninhabited for centuries.

You are able to identify locations where houses and churches once stood, but the vegetation on the island is so overgrown that it is nearly impossible to tell where one crumbled building ends and another begins. What do you do?

This is the problem that Nick Rauh and his Turkish research partners confronted over the last several summers while working on Dana Island, a small Mediterranean island located less than two miles off Turkey’s southern coast.

“When we’re working in it, we’re stumbling over wall fall and we’re looking at cisterns and we’re looking at walls, but we have no idea how they’re running,” said Rauh, a professor of classics. “Does this quarry pit go all the way to the shore or is it just a local thing right here? And there’s another pit 20 feet away. What’s the relationship between the two? Are they connected in some way?”

Physically clearing the areas around these ancient historical sites could help answer these questions, although that is a particularly painstaking process. But what if the researchers could make all of this vegetation disappear without clipping a single branch?

Enter ROSETTA.

A team of Purdue researchers recently proved that archaeologists can analyze a site digitally, by making use of drones armed with cutting-edge LiDAR sensors.

“With the drone, we can map the entire area, map the vegetation separately from the ground, and remove the vegetation so that we can see what’s underneath,” said College of Liberal Arts Associate Dean for Research and Graduate Education Sorin Matei. “That’s a quantum leap in research.”

Dispute over settlement's age

Matei coordinates the ROSETTA (Remote-sensing technologies and techniques in archaeo-anthropology) initiative of which the Purdue research team is a part. The ROSETTA group aims to establish the time period when the island was inhabited – a source of debate within Turkish archaeological circles.

Rauh’s Turkish project director Günder Varinlioğlu – associate professor at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University in Istanbul – says the structural remains, such as six churches, indicate that the island was in use during the late Roman era. However, a competing archaeologist argues that the quarries and building foundations along the coast are what is left of ancient shipyards that date back to the Bronze Age, making the settlement roughly 1,000 years older than what Varinlioğlu’s research indicates.

“This archaeologist and my director have been giving sort of dueling-banjo annual reports for the last four years about this island, and the presentations are so starkly contrasting that it really has created a major controversy among the archaeological community working in Turkey,” said

Rauh, an ancient pottery specialist. “It hasn’t resonated over here, but over there it’s kind of a big deal, and people in Europe know about this, as well. So it’s making its way west, I suppose.

“But there is this issue: Was it this early Bronze Age thing or, based on what we see, was it kind of a Christian era? Because what we see is that about 75-80% of the pottery is late Roman. There’s very little prior to that.”

Among the most noteworthy characteristics of this island are the extensive stone quarries that have supplied ordinary building material for construction projects across the region. As such, Dana Island is a unique case where the ancient stone industry existed side-by-side with the settlement of the workers and quarry owners.

“This is not just a regular maritime settlement of late antiquity. It’s a major industrial settlement which includes not just the quarries, but also the settlements where the workers and the owners of the quarries, maybe, had lived,” Varinlioğlu said. “You have the industrial area – the quarries and the ramps, which allowed the inhabitants to export the stone to other places – so it’s a commercial center from an industrial point of view, not just from a trade-of-commodities point of view.”

But do the quarries also belong to late Roman era as suggested by the pottery, the churches, and numerous other buildings.

The Purdue team believes geology graduate student Angus Moore can establish a time period for the quarries using an exposure-dating technique on rock samples he cut while on the island.

Moore cut samples from the outside corner of a stone quarry that is fully exposed to the elements, as well as from an inside corner that is essentially shielded from the cosmic radiation that rains down upon the earth’s surface. By comparing the concentration of cosmogenic nuclides in the unshielded sample to the concentration from the protected corner sample, Moore believes he will be able to ascertain when the quarry cut was made.

“It seems like there’s very thin evidence that the quarries are really [from the Bronze Age], although this archaeologist has made a big to-do in Turkey about it,” Moore said, “so I think it’s really important that we get some independent age constraint to try to settle that issue as quantitatively as we can.”

The researchers believe that Moore’s dating method can determine within about 200 years when the cutting occurred, which will be more than sufficient enough to settle the debate over when the settlement existed.

“That’s really what I’m hoping,” Rauh said. “That was the mission as far as I’m concerned.”

Once the Turkish government cleared the samples to leave the country, Varinlioğlu was able to bring them to Purdue on a January 2020 campus visit. However, the COVID-19 shutdown delayed by several months Moore’s opportunity to access the lab where he would conduct the necessary sample analysis. He hoped to continue his testing during fall 2020.

New use for drones

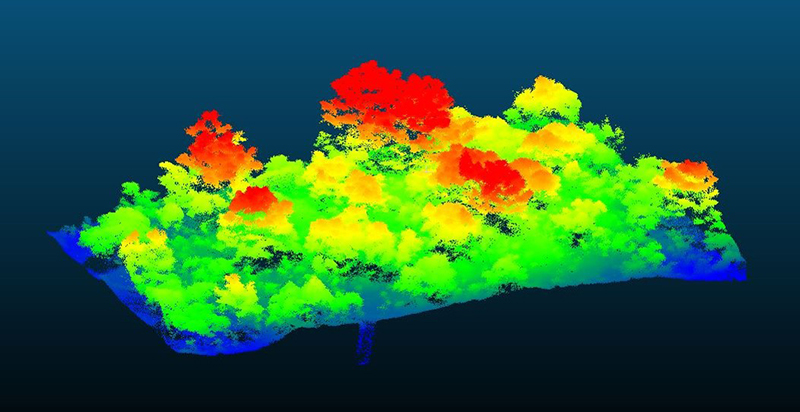

Drone photography is not particularly unusual at an archaeological site, but the Purdue team added a new dimension to this practice by incorporating LiDAR into its image-gathering process. A LiDAR unit mounted to the drone scans the area below with 32 laser beams, creating a pointcloud with millions of individual points that collectively generate a 3D image of the ground.Thomas A. Page Professor of Civil Engineering Ayman Habib traditionally uses drone imagery to study corn and sorghum crops, conduct bridge safety inspections, or to assess automotive accidents in cooperation with the Tippecanoe County Sheriff’s Office. Using a drone for archaeological purposes was entirely new to Habib and drone pilot Evan Flatt when they traveled to Dana Island to assist the research team for four days in the summer of 2019.

“For me, it was quite interesting,” Habib said. “To be on a site where basically we see some walls or pottery that’s maybe 5,000 or 6,000 years old, it’s quite impressive. I have never been on a site actually where we did something similar.”

The images from Habib and Flatt’s drone flights were so in-depth that it stunned the archaeological researchers. After reviewing their results, Rauh drew a new conclusion about the size of the settlement that existed on the island.

“All the way along, there are houses and other types of buildings, churches, whatever it is,” Rauh said. “And so to see what looked like at least four terraces, it suddenly registered in my mind this was a much bigger-built environment than I had realized. How big I don’t know.”

Added Varinlioğlu: “It has facilitated our work a great deal. We have seen features that we were unable to see before. Maybe you go there, you map it, or you see it but you cannot coordinate it. You cannot match it with everything else. So it provides a global coverage that human beings are unable to do in the field.”

Not only were Habib and Flatt able to provide a clearer picture of the ruins that exist underneath the vegetation, their drone imagery penetrated beyond ground level.

The LiDAR identified hundreds of cisterns across the island where residents once stored drinking water. The 3D imagery shows spikes below the surface that pinpoint cistern locations.

“I was really surprised that we were able to get the laser penetration actually inside the cisterns where we could even in some cases get an idea of the shape of the inside of the cistern and definitely the depth and just basic dimensions like that,” said Flatt, senior research engineer in the Lyles School of Civil Engineering. “That was really interesting – something that would take hours to just walk around the island, find these holes in the ground and then try to measure them. So just with a quick 10-15-minute UAV flight, we were able to find quite a few of them, and just briefly looking at the data, we could see them.”

This shows how introducing 3D LiDAR technology can be revolutionary at archaeological sites like Dana that are overgrown with dense vegetation, preventing satellite imagery from being effective. Beyond the high-resolution layout of the island that LiDAR can provide, it can also reduce researchers’ need to take time-consuming measurements by hand.

“The main thing that we’re accomplishing with the drone is we will have a complete photographic record of what’s there,” Rauh said. “And then the process of interpreting that and planning that and identifying the features on that can go on progressively without having to go, necessarily, to the island.”

Varinlioğlu noted, however, that the technology is a complement to – not a replacement for – the important work that archaeologists do by hand at research sites.

“I think it’s extremely invaluable to use new technologies in archaeology, but I just do not want to undermine the importance of human presence in the project,” Varinlioğlu said. “Technology is going to do things that we are not able to do, but then humans and machines have to collaborate. I would never imagine doing archaeological projects just remotely. I do not think this is possible, and this is not the nature of archaeology. Human perception, human interpretation, and human recording is extremely important and these should be together. And that’s why I think the collaboration between archaeologists, engineers, and remote-sensing specialists is extremely important.”

Rough terrain

Limiting travel to the island when possible is likely for the best. Dana Island looks pleasant enough in photos, surrounded by the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean. However, the actual conditions there are somewhat brutal.The research team had to wake before sunrise each day and take a 4:30 a.m. boat ride to the island in order to arrive by 6 a.m. They would work there until around noon in an effort to complete their daily assignments before the summer heat got too intense. Once on the island, its razor-sharp rocks along the shoreline and hilly topography made it challenging for visitors to maneuver about the island.

For this reason, Rauh likes to bring Purdue ROTC students to assist the researchers, knowing they will be better equipped to handle the island’s inhospitable environment.

“Sitting down was terrible because if you sit down in the brush or in the pine needles, there’s bugs in there or maybe snakes,” said ROTC student Zoey Osterloh, a mechanical engineering student. “But then if you want to find a rock to sit on, all the rocks are pretty jagged.”

Osterloh said she and fellow ROTC student Kenny Klimek were “like the mules of the team,” clearing brush for the graduate students and other researchers on the team who numbered as many as 20 at points. Obviously a little military toughness came in handy.

“I brought my combat boots. It was pretty comfortable walking around,” said Klimek, an industrial engineering student who as a freshman accompanied Rauh on a more conventional study abroad trip to Greece. “I really enjoyed the hiking. It was pretty physical.”

Varinlioğlu hopes to eventually make Dana Island a more inviting destination. In association with the Boğsak Center for Archaeology and Heritage that she is developing in the nearby village where the researchers have resided since the beginning of the project, she wants to open the island to visitors who will walk cultural trails connecting notable settlements and learn about ancient architecture, technology, and industry.

The island’s current lack of walking trails and its steep-sloping hills made things difficult for the drone team, in particular. They struggled to find flat surfaces where they could launch and land the UAV and consistently worried about crashing it into the trees on the hillside, neither of which are concerns when conducting traditional drone research at Purdue’s Agronomy Center for Research and Education.

“All our work for the last few years has been over flat area here in Indiana, agricultural fields. We don’t have any obstacles nearby,” Habib said. “This data set or this data acquisition was quite challenging in that we had a relatively steep slope of the island, and it’s very hard from where we are on the shoreline to figure out how much clearance do we have between the drone and the vegetation.”

There were times where the drone team deployed a second, smaller drone to scout an area, determining whether the bigger drone would have enough room to operate. Rauh offered manual assistance at other times, climbing to an elevated point along the hillside and calling back to the shore by cell phone to communicate the distance between the drone and the trees below.

ROSETTA opportunity

Teamwork is what the fledgling ROSETTA project is about, after all.Matei envisions ROSETTA as a hub for research innovation in the social sciences and humanities, enhanced by the technological capabilities offered through engineering and artificial intelligence. He hopes to use the collective to foster further interdisciplinary collaboration – one of the most appealing aspects of the project for the scholars who worked on Dana Island.

“As a methods guy, you’re always looking for different ways to apply methods, different problems to work on,” Moore said. “It’s always fun to have something like this come up where you get to collaborate with people who you wouldn’t usually get to collaborate with and apply a method in a new way to a new problem that’s really interesting and exciting.”

Added Rauh, “the main thing is that we’re coming at it from different angles and you can get this, ‘Oh you know, this technology might work for solving the problem that you’re facing right there.’ OK, what is this technology about?”

This is where breakthroughs can occur, by connecting experts from vastly different disciplines who may never cross paths without a project like ROSETTA serving as a conduit for collective discovery.

“Purdue has always been a home for interdisciplinary research. We always tried to connect researchers across units,” Matei said. “With this initiative, what we’re doing is to go to the next level where we create research teams and discovery teams that are the principle investigator because the instrumentation of the project demands that people work very closely together to make this happen.

“So in this respect, ROSETTA is also an attempt to rethink the act of research itself and the issue of research ownership, which now is moved from individuals to groups.”