Part Two: On the role of the arts and humanities in Purdue’s early days

Graduate training and literary societies in Purdue’s early days

Alongside the myth that liberal studies were inessential at early Purdue, I have often heard it said that Purdue did not offer graduate training or graduate degrees in English and history until the 1960s. The truth is that Purdue was offering graduate work and conferring graduate degrees in the humanities in the early years.

The 1893-94 annual, for example, lists Edith Heath Hull, who received her BS in 1891 at Purdue in literature and art, as a candidate for the degree of MS. She is listed as a “resident graduate” living on North Ninth Street in Lafayette. Other resident students include Clara Maud Rittenhouse, BS ’93, literature and art, a candidate for degree of MS; Mary Weekly Royse, BS, candidate for degree of MS; and Agnes Eugenie Vater, BS ’91, MS candidate in psychology and literature. Non-resident graduate students pursuing liberal studies include Mary Katherine Hollingsworth, BS ’91, and John Breckenride Burris, BS ’88.

For resident and non-resident students alike, Purdue in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a place where you could receive a four-year degree in the liberal arts. Humanities thesis topics for the BS degree in 1904, for example, suggest a degree of cosmopolitanism, sophistication, and international focus that does not fit the myth of Purdue as a Midwestern “cow college.”

Lyla Vivian Marshall wrote her thesis on French Impressionism, Ell Mable Shearer wrote on character in George Eliot’s “Adam Bede,” and Lois Eva Yager on Ruskin’s “Seven Lamps of Architecture.” Muriel Joy Alford wrote on “Victor Hugo, the Lyric Poet and Novelist” and Bernice Hazel Baker on “The Literary Influence of Madame de Stael.”

One could go on from the bachelor’s level to study at the master’s level, which, at that time, was the qualification to teach at the college level, not just at upstarts such as Purdue, but at most colleges and universities at the time. Graduate students in the humanities were writing theses on literary and cultural topics that one might assume were undertaken in 2004, not 1904.

An MS in 1904, for example, was awarded to Gusta Wilhelmina Felbaum (BS) for “Wordsworth’s Sensuous Endowment as Shown by the Images he uses in ‘The Prelude.” In 1904, Cecil Clare Crane’s thesis was on the “The Life and Works of George Sand” (a female author), and Jewell Martz Harbaugh wrote on “The Art of Narration as Shown in ‘The Master of Ballentrae’.”

It is notable that Purdue was offering graduate training in the humanities in the late 19th century. As Gerald Graff reports in “Professing Literature,” his “institutional history” of how English has been taught in U.S. colleges, graduate study in English in the United States in the 19th century was “virtually nonexistent.” “By one estimate, in 1850 there were eight graduate students in the United States. By 1875, a year before Daniel Coit Gilman established Johns Hopkins as the first American research university, there were only 399.”

We should not interpret the fact that Purdue did not offer the BA or the MA degree in the early years as indication that Indiana’s Land Grant did not offer degrees at the bachelor and graduate levels in the liberal arts. The BS and MS abbreviations refer to what today we regard as degrees in an arts and sciences college.

One might turn to the 1910-11 catalog to get a better feel for what Purdue faculty and administrators meant by a “School of Science”: “The School of Science provides introductory and advanced courses of instruction in the sciences and in those other subjects that are essential to a broad scientific education – Drawing, Economics, English, French, Human Physiology, German, History, Mathematics, and in Household Economics and Art.”

Reading this description, my sense is that Purdue, in the first decades of the 20th century, was wrestling with a complex and evolving sense of its mission. On the one hand, the university maintained the umbrella term “science,” but acknowledged the “essential” value of a “broad scientific education.” Math, art, and literature are grouped together in the arts and sciences programming that awarded the BS and MS degree.

The separation of these areas of study distinguishes the liberal arts and sciences from what were perceived in the early days as vocational/technical training areas such as agriculture and engineering. The goal was not to separate the arts and sciences from each other, but rather to associate the arts and sciences together in the “stem” sense of connectivity, rather than the “STEM” sense of separation.

The 1891 “Debris” – Purdue’s yearbook – underscores the prominence of art as a discipline that combines theory and practice in an educational endeavor that seeks to apply an appreciation for aesthetic beauty with the design of useful objects for everyday living produced by local artists:

THE SCHOOL OF ART It is the purpose of the Art Department of Purdue University to give to the students some practical ideas of how to apply a knowledge of drawing to actual work. This is not a school wherein students paint pictures or portraits, but the department might be called one in which artistic artisanship prevails. Drawing from the model is compulsory before wood carving or china painting is begun. Drawing trains the mind, the eye, the hand, and when these three work in harmony, seeking, seeing and portraying ideal conceptions of one's surroundings, then to humble things may be ascribed beauty and grandeur. With the march of progress higher technical education is demanded. A place is made and waiting in the school-room for wood carving and china painting, the arts perhaps the oldest known to man, but ever susceptible of new life.The 1907 “Debris” notes that Art Professor Laura Anne Fry, herself a renowned ceramicist who was among the first designers for Cincinnati’s Rookwood Pottery, “directs the work in drawing and painting. Besides instructing her students in the ‘eternal fitness’ of things in the decoration of china, she gives lectures on art in a broader sense, keeping her students in touch with the work of great artists and advocating the adherence to the artistic in everything.”After teaching the students the principle of cutting, they are shown the practical side of their work, and ornament useful things. This carries with it the ability to make attractive and to beautify the things of daily life […] China painting is the recent addition to the art department, but home as his or her gift to the University the work will bear witness as to its success. Although to some members of the class it was a new thing, they entered into the work with the enthusiasm of the connoisseur. It is no longer a surprise to find a lady’s table set with dainty decorated wares, not imported, while she has the perfect pleasure to confess that the same is her own handiwork.

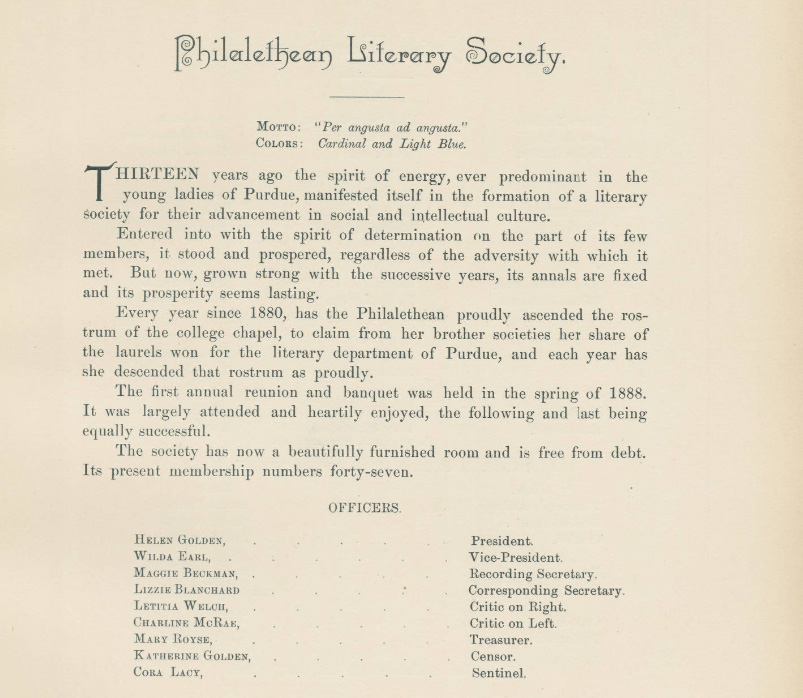

The 1903-04 catalog paints a picture of Purdue as a place that in some ways resembles a hotbed of humanistic activities that one would associate with an Oberlin or a Kenyon as much as an MIT or a Georgia Tech. The catalog, for example, boasts the then-small school, numbering in the hundreds, not thousands, of students, featured no less than four literary societies: the Irving Society, for men only; the Carlyle Society, for men only; the Emersonian Society, for men only; and the Philalethean Society, for women only.

The “Debris” yearbook from 1891 devotes multiple pages to the histories of the literary societies. Here is a sampling from the description of the Emersonian Society:

Emersonian Literary Society was called into existence to afford intellectual and social culture to that body of young men whose ambitions were not satisfied by simply pursuing the college course. Through self-imposed duties, literary and elocutionary abilities were to be developed; through contact with a limited number, the social nature was to be refined. The Society was not called into existence in a moment, but as the result of deliberate thought and full knowledge of the difficulties to be encountered, both in the work necessary and the unsatisfactory quarters that must be accepted. Coming as it did at the demand of men, it may be said to have been born an adult, and, although an infant in years, it bears its burdens by the side of its brothers and receives its due reward.Here is a sampling from the “Debris” report on the Philalethean Society:

During the fourteen years of her existence, [the society history] has been many times recorded; these histories have been narratives of success and triumphs, increasing with the years, and thus proving that the young ladies have faithfully carried out their motto," Per angusta ad augusta” [translation: “through difficulties to honors”]. During the present school year the membership has been thirty-five. Much has been expected of the Society, but the expectations have been realized, for what cannot thirty-five girls do? The success of the drama, "Tom Cobb, or Fortune's Toy," given under the auspices of the Philaletheans, but with the kindly aid of her brother societies, is still remembered with a feeling of pride by those interested in the welfare of the Society, and one of pleasure by the general public. The young ladies, as was confidently expected of them, bore their share of the honors during the annual entertainment given in April.And here is a snippet of the “Debris” page on the Carlyle Literary Society, which suggests the Carlyles came into being because of their disagreements with the Irving Society:

The men who organized this new society were what was known as the "faction" of the Irving. Internal convulsions and dissensions in the Irving brought matters to such a crisis that these men felt that they could no longer, conscientiously, remain members of the Society. Their resignations were immediately tendered and steps for the organization of a new society were taken. At this first meeting the name of Carlyle, after the great English author, Thomas Carlyle, was adopted as the name of the Society. The Constitution and By-laws were also approved and adopted. The first meetings were held wherever a room could be obtained. After some time, by action of the Board of Trustees, half of the present room was offered them. The Philaletheans not being averse, an agreement was made by which the two societies occupy the hall in common. The carpet, piano, curtains and other decorations are the joint contributions of the two societies. Our record is one of which we may be proud. We have always been progressive in our views and actions. Many decided novelties have been introduced by us—decorations for annuals, mock trials, society hops, society picnics, and the Oxford cap and gown are among the novelties introduced by Carlyle. Our annuals and other public entertainments prove how high literary perfection has been carried by the Society.The robust literary society culture, evident in the pages of the “Debris,” encouraged the creative endeavors of early students such as George Ade, John McCutcheon, and Booth Tarkington. These three students would go to make their mark on the national stage as leading cultural figures, and, in a literal sense, left their mark on the Purdue campus as Ade, a major benefactor, helped fund the football stadium now known as Ross-Ade, and McCutcheon’s and Tarkington’s names now adorn Purdue dormitories. McCutcheon, a prize-winning editorial cartoonist for the Chicago Tribune, also has been honored with a high school in Tippecanoe County being named for him.

I hope my study into the robust activity in the humanities in Purdue’s early decades will serve as my contribution to the ongoing process of honoring the contributions, not only of eminent alumni such as Ade and McCutcheon, but also of the faculty and campus resources that enabled their growth as creative minds when they matriculated at the West Lafayette campus more than one century ago.