Part One: On the role of the arts and humanities in Purdue’s early days

A robust curriculum and dedicated faculty in the humanities

A Purdue English professor since 1994 with a specialty in poetry analysis and literary criticism, I sometimes find myself wondering about the history of my disciplines at a leading STEM-oriented university.

As Purdue celebrated the anniversary of its founding more than 150 years ago, I became increasingly curious to know if Indiana’s Land Grant has always been as STEM-centric as it has now become? What exactly was the role of the humanities during Purdue’s early decades?

To find out, I spent many hours in the university library archives, combing over early catalogs, yearbooks, interview transcripts, press releases, and other annual official documents. Here is some of what I discovered: Most certainly, Purdue emphasized what we now regard as STEM fields from the early days, but there was, as well, a significant focus on humanistic endeavors from the start.

“A thorough knowledge of one’s own language is deemed of highest importance; therefore, instruction in English forms a proper proportion of the work throughout all the courses of study,” states the “Modern Language” annual register of 1874-75.

There was a sense of joint effort, a connectivity between humanistic and scientific studies implicit in the words of Annie S. Peck, instructor in Latin and Elocution, who offered her summary report on “Latin Studies” for Purdue’s 1882-83 annual register:

In a language where the change of a single letter alters the entire construction of a sentence, much closer observation is demanded. Careful attention to forms becomes habitual and is of material service in correcting the heedless method of reading English which gives rise to the poor spelling everywhere so common. To cultivate habits of observation and accuracy in one department is to exert an influence of the character of the greatest value in practical affairs. The power of judgment and ready inference receives continual exercise in this study, to a degree unequaled anywhere; and it is these qualities of observation, accuracy, judgment, and ready inference which are the most essential elements of success in any trade or profession. Furthermore, to the scientific student especially a knowledge of Latin roots and terminations is of great practical value.Peck’s comments from the annual register suggest that founding Purdue faculty designed an interconnected liberal arts and science curriculum in the late 19th century. It is clear from Peck’s report on Latin studies in the 1882-83 annual register that she was a curricular reformer and pedagogical researcher who advocated for the interdisciplinary role of classical studies at a land-grant college.

In fact, her graduate mentor (and later president) at the University of Michigan, James B. Angell, is credited by Gerald Graff – the leading researcher into the history of literature study at American universities – with renovating classical studies away from the mind-numbing recitation version of language learning that Angell had observed when teaching at Brown in the 1840s.

Following Angell’s model at Michigan, Peck brought cutting-edge pedagogy to Purdue in the early 1880s. She served as an articulate and provocative spokesperson for what we today celebrate as interdisciplinarity. As Peck’s testimony from the 1882-83 register about the value of Latin demonstrates, archival research into Purdue’s early decades enables us to remember that the humanities at Purdue were an essential aspect of the mission of Indiana’s land-grant university. Humanities at Purdue were never an afterthought.

From the start, Purdue required students to have a robust, even comprehensive, foundation in the liberal arts. According to the 1874-75 annual register, for example, students in the School of General Science, “are required to spend about five terms in the study of French and seven terms in the study of German.” The annual states, “It is intended that these languages shall be pursued to such an extent and with such thoroughness that the student may read them readily and translate them freely.”

One may argue that the early faculty designed such language requirements to facilitate the reading of scientific journals in French and in German. Nonetheless, as the 1877-78 annual register indicates, the study in German includes substantial training in world literature: “in the Junior year, Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell and Mary Stuart, Goethe’s Egmont” and in the Senior year, “Goethe’s Faust” and “History of German Literature and Language (by lectures).”

The 1876-77 annual register indicates even rudimentary language instruction in English is undertaken to facilitate advanced study in literature. “A student who has not acquired creditable skill in the use of his vernacular, is poorly prepared for the study of its literature.” The 1877-78 description of the course in Latin suggests extraordinary levels of intensity, sophistication, and prolonged training for an undergraduate program:

The course in Latin includes, in the Freshman year, the Grammar, the Reader, and Prose Composition; in the Sophomore year, three books of Caesar, seven orations of Cicero, and Prose Composition; in the Junior year, six books of Virgil, two terms, and De Senectute, one term; in the Senior year, Livy, one term, Horace, one term, and Tacitus, one term.Study in English literature, as the 1881-1882 annual register reports, is, like the Latin program, rich in challenging reading materials and critical response writing assignments. “The course for the past year has included a critical study of Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet,’ selections from Scott’s ‘Lady of the Lake,’ and Byron’s ‘Prophecy of Dante.’ The class exercises have included many carefully written essays on the lives and literary characteristics of distinguished authors.”

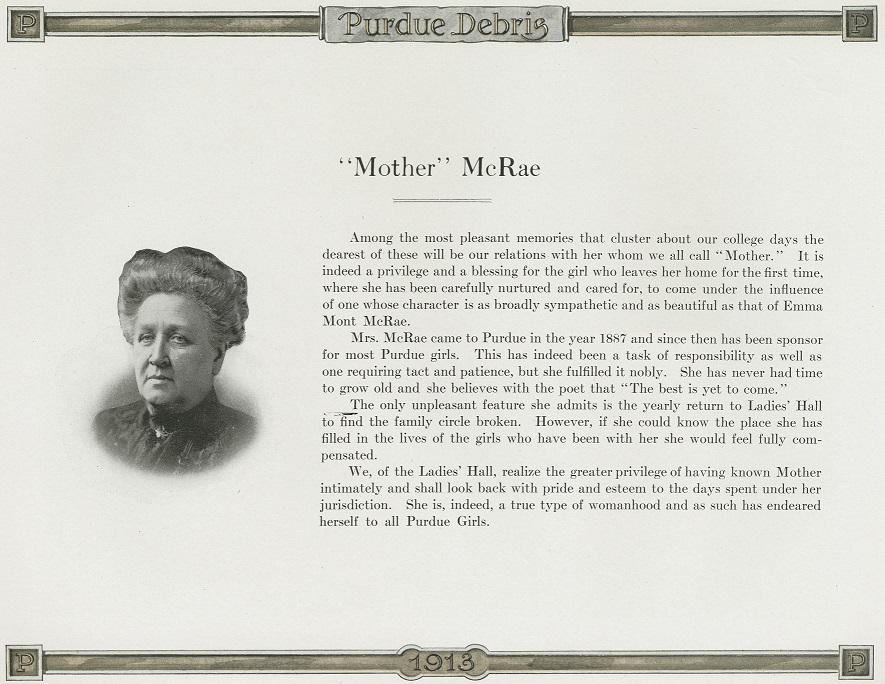

The 1893 annual’s description of “Literature” in the “General Studies” category offers a detailed report of the four-year program. Presumably written by Emma “Mother” McRae, the long-serving, unofficial “dean” of women and professor of English whose name is listed beneath the “Literature” heading prior to the course offerings, freshman-year readings include Shakespeare’s “As You Like It,” Arnold’s “Soharb and Rostum,” Milton’s “Comus,” “L’Allegro,” “Il Penserose,” and Ruskin’s “Athena, Queen of the Air.” Whereas English studies are required for the first three years, an elective fourth-year course in English literature features “typical works of Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton, Pope, Wordsworth, Shelley, Browning, and Emerson (that) are studied in detail.”

Need I acknowledge that we are dealing here with an exclusively white, male, primarily British, high-cult literary canon? Even defenders of the “Western Canon,” such as the late Yale literature scholar Harold Bloom would today struggle to defend the exclusivity apparent in early Purdue reading lists.

My sense is that the canonical reading lists at Purdue, however elitist, were part of the land-grant experiment in the democratization of higher education movement in the United States after the Civil War. Since the founders designed land grants as institutions to promote social class uplift, the canon served to confer what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu calls “cultural capital” to the rural working class and rising middle-class sons and daughters of the Hoosier State.

Uncomfortable with the white male canon put forward in the late 19th-century Purdue reading lists, I remain impressed with how early Purdue faculty offered a range of critical approaches to the classic texts. I should add here that by the 1904-05 annual register, Purdue English studies includes work by women – George Eliot’s “Silas Marner” – and American texts such as Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography and poetry by James Russell Lowell.

First-year instruction at Purdue in 1882-1883 focuses on literature “as illustrations of rhetorical principles.” Sophomore-year studies echo Matthew Arnold’s aestheticism and evaluative approach in the preface to “Culture and Anarchy,” in which the Oxford Professor of Poetry states:

The whole scope of this essay is to recommend culture as the great help out of our present difficulties; culture being a pursuit of our total perfection by means of getting to know, on all the matters which must concern us, the best which has been thought and said in the world, and through this knowledge, turning a stream of fresh and free thought upon our stock notions and habits, which we now follow staunchly but mechanically, vainly imagining that there is a virtue in following them staunchly which makes up for the mischief of following them mechanically.The Purdue annual notes that sophomore-year studies aim “to cultivate a taste for what is best in literature, to show the student where to look for the best, and to teach him to distinguish it from the second best and the inferior.” Junior year focuses on prose, historiography, autobiography, and stylistics with writings including DeQuincey’s “Confessions of an English Opium-Eater” (Mother McRae, what were you thinking?!), as well as work by Macauley and Carlyle.

A sign of how early faculty sought to provide an interdisciplinary, holistic, and Deweyan pragmatic approach to language studies may be noted by the additional comment in the “Junior Year” course description: “Three original papers upon subjects will be required of Engineering students during the year.” Combining critical approaches to literary studies, including the autobiographical, contemporary contextual, and philosophical, the description of senior-year work adds to the rhetorical, aesthetic, and historical approaches that have been developed in the first three years of study: “These works are studied in the relation to the lives and characters of their authors, as well as for the light they throw upon contemporary life and events. An attempt is also made to indicate the relation of each of these great writers to the development of modern thought.”

Basing my judgement on the state of English studies in the United States in the late 19th Century as characterized in Graff’s standard account, “Professing Literature: An Institutional History,” I would say that Purdue’s four-year program in “Modern Languages” compares well to programs at established East Coast universities of the period. In some ways, Purdue’s variety of critical approaches, active student engagement in learning in ways besides recitation, and breadth of texts under discussion surpasses Yale’s program at the time.

Graff reports that a “modern language scholar recalled in 1895 that at Yale he had ‘passed through four years of a college course without once hearing from the lips of an instructor in the class-room the name of a single English author or the title of a single English classic’” because Yale faculty considered modern languages to be “frivolous subjects” in comparison to Greek and Latin. By contrast, we see the land-grant upstart in West Lafayette embracing both modern and classical studies.

Whereas “the recitation method remained in force” at most U.S. colleges and universities at the time of Purdue’s founding, and, literature “was subordinated to grammar, etymology, rhetoric, logic, elocution, theme writing, and textbook literary history and biography,” we see in the Purdue “Modern Language” annual register a combination of the approaches Graff lists above with a greater emphasis on the relationships of reading, writing, and thinking: “The instruction in language aims to proceed upon the principle that language is the expression of thought.”

As Purdue’s enrollment grew, so did the faculty in liberal studies. In 1876-77, Purdue had 10 faculty. Of the 10, four positions are devoted to the humanities and the arts. Emerson E. White, the president, is listed as professor of English literature. He is joined by Edward P. Morris, instructor in Latin and history; Robert F.H. Weyher, instructor in German; and William Mohr, instructor on the piano.

The 1877-78 bulletin lists nine faculty, with White, again as president and English literature professor, as well as Charles E. Lambert, instructor in Latin and history, and R. Weyher, instructor in German.

1883-1884 marked the 10th year Purdue published a registrar bulletin that listed faculty and courses. Among the 14 faculty members listed are President James Smart and Edward E. Smith, a professor of English and history. The annual also lists the renowned future author and Purdue benefactor George Ade in the freshman class. The “Prepatory Class” is required to take a “thorough drill in the common English branches” as preparation to enter one of the four main schools.

More than a century ago, in 1904-05, Purdue’s faculty in literature, language, history, and art, were growing, not diminishing, in status and visibility as the young university formed its initial identity as a comprehensive Midwestern land-grant institution.

Faculty in these areas reached 15 members by 1904-05, more than doubling the six members listed in 1893-94. By 1913-1914, the English department alone had a teaching staff of seven, with Professor Ayers listed as “in charge,” and then a staff of six other faculty who served at the associate, assistant, and instructor rank. By 1916-1917, the English department course offerings are robust, and, in fact, not so different from what the department would offer a century later.

The teaching staff of 10 – including two full professors, four assistant professors, and four instructors – taught 18 different course titles, ranging from first-year English, to courses in English poetry, English prose, the novel, argumentation, 19th century prose, Shakespeare, Browning, and Tennyson, public speaking, advanced composition, and American literature.

A decade later, it is obvious that the English department has secured its place as a significant part of the university. In 1926-27, the English department alone had a teaching staff of 20 (with one on leave). The department had begun to resemble a contemporary unit with three full professors, two associates, seven assistants, and 10 instructors. The pedigree of the faculty now boasts graduates of the Ivy League – Herbert Creek from Princeton and James Hugh McKee of Columbia – as well as faculty with training and advanced degrees from established Midwestern flagship state universities including Illinois, Indiana, and Missouri.

There is anecdotal evidence that literary studies were neither an afterthought at the university’s founding, nor merely a service dimension to a STEM education as the university took roots and grew into a major university in the first half of the 20th century. Here is a passage from a 1970 transcript I found in the university archives in which the interviewer (Eckles) asks a longtime English faculty member (Richard Cordell) about the Purdue department in comparison with other Big Ten departments:

Cordell: I don't think we compared very well for a number of years. But I remember in the 1940s during one week two book men from big New York publishing companies came around, and both said the same thing: “You know that Purdue’s English department has one of the best reputations in the United States for publications by its staff members.” But it took a long time to get there. When I was at the University of Singapore in 1964According to the interview with Cordell, the English department staff numbered between 80-100 full-time faculty members in the 1960s. (By comparison, the current version of the Purdue Department of English numbers around 60 members).Eckles: You taught there?

Cordell: Oh, no, I just gave one lecture there. I was a guest of a friend, an Englishman, who was teaching there. But I found that Purdue was well known among all the graduate students in English at the University of Singapore, because of the periodical, Modern Fiction Studies. Students went around carrying it almost like a Bible.

Eckles: It was edited here, wasn’t it?

Cordell: It still is, too.

Writing in 1970, Cordell remembers the department was actually somewhat larger in the past, before graduate students started to teach first-year classes. Cordell speaks with pride about the growth of English and the humanities at Purdue. He notes how English could schedule classes independently of the needs and interests of the engineering department.

Cordell remembers that, aside from the fact that Purdue does not own many prestigious literary papers aside from Indiana authors, he feels, circa 1970, that the English department compares in quality to Illinois and Indiana.