The Work of Civil Society at the Paris Climate Summitby Robert Marzec

The 2015 Climate Summit took place in Paris this past December. Its main political goal was to generate a binding agreement between 196 nations capable of keeping humans from exceeding a 1.5-2.0 degrees Celsius global temperature rise above pre-industrial levels.[1] 1.5-2.0 degrees may carry little meaning if you aren’t at least somewhat knowledgeable about climate change, but keeping global temperature rise to a minimum is crucial to saving the planet from a grim future.

Such an increase in global temperature may appear slight, but the smallest of temperature increase impacts ecosystems around the planet. Above 2 degrees risk increases dramatically on melting ice caps, sea-level rise, weather patterns, and regional climate, which in turn effects water and food security, human and nonhuman migration patterns, national stability, and life in general. A 17 percent loss of land in Bangladesh—now a most likely scenario by 2050—would displace 18 million people. Even a 1.5 degree increase will have serious effects on sea-level rise, and not only on delta regions in Bangladesh, Egypt, Nigeria, Thailand, and the Mississippi, but coastal cites like New York, Calcutta, Shanghai, and San Francisco. Sea levels have already risen by 6.7 to 8.3 inches since 1901, and are expected to rise an additional one to four feet by 2100. Most island nations, like the Marshall Islands (less than 6 feet above sea level), will not make it.

In the face of such deeply-rooted patterns of human development, expecting heads of state to solve our ecological dilemma is a bit like expecting Hamlet to make a decision before the final act. Hence the importance of the other half of COP21—the civil society or “Climate Generations Area” of the conference.

I traveled to Paris this past December to attend these “side events” of civil society. Set in immediate proximity to the official political negotiations, the Climate Generations space (“l’espace” is the official French term) is COP21’s venue for non-state actors: organizations like the International Indian Treaty Council, the Indigenous Coordination of the Brazilian Amazon, the International Water Association, the European Trade Union Federation, the Nature Conservancy, the World Resources Institute, the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts (yes, the Girl Scouts), and dozens of others in addition to scientists that specialize in climate change. Touted as the “first in the history” of the “climate conference organization” and the result of more than a year of consultations with 117 civil society organizations from around the planet, the Generations space brought approximately 360 organizations and international associations for over 340 sessions, multiple interactive educational exhibits, numerous art installations, and over 60 film screenings.

this past December to attend these “side events” of civil society. Set in immediate proximity to the official political negotiations, the Climate Generations space (“l’espace” is the official French term) is COP21’s venue for non-state actors: organizations like the International Indian Treaty Council, the Indigenous Coordination of the Brazilian Amazon, the International Water Association, the European Trade Union Federation, the Nature Conservancy, the World Resources Institute, the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts (yes, the Girl Scouts), and dozens of others in addition to scientists that specialize in climate change. Touted as the “first in the history” of the “climate conference organization” and the result of more than a year of consultations with 117 civil society organizations from around the planet, the Generations space brought approximately 360 organizations and international associations for over 340 sessions, multiple interactive educational exhibits, numerous art installations, and over 60 film screenings.

Walking into the COP21 exhibition located at Le Bourget (the north-east fringe of Paris, where Charles Lindbergh ended his solo transatlantic flight in 1927, and where Hitler began his tour of occupied Paris in 1940) I was immediately struck by its Spartan design. [photo 1] This was the opposite of the kind of architecture for which Paris was famous. Nothing like the Grand Palais exhibition center, with its art nouveau hall and domed glass roof. And nowhere near the glamour of the temporary sites of the famous Paris Expos of the 19th and 20th centuries. But abstinent aesthetics was mainly the point at Le Bourget: the almost Puritan structure that housed the side events was based on the best practices of an eco “circular economy,” with open scaffolding and naked pressed wood walls made from sustainably-managed forests adorned with only scientific posters, room numbers, electronic displays, and artwork limelighting the urgency of global warming. Any other materials were either reusable or rented, and anything newly-purchased—like tables, chairs, visual displays—would be donated to local associations, schools, and public libraries.

Sessions addressed the full range of climate change issues: REDD+ programs (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation), climate change curriculum from kindergarten to college, gender equity, infrastructure, biodiversity. The Lucie Foundation curated an exhibition of photographs: from the realism of men, women, and children scavenging in Port au Prince’s burning wasteland for sellable plastics, clothing, and aluminum (to make, optimistically, $12 a day), to the symbolism of fish carcasses on dinner plates sitting in the parched, cracked earth (the global water shortage is now “chronic” according to the UN— more than half of the counties in the US are low on water). There was even music: drum songs opened the first Indigenous session, and the DJs at the SolarSoundSystem (run by the “muscle power” of conference attendees on bicycles instead of its touted photovoltaics, since we weren’t out in the sunshine) spun an international mashup everyday from 11:00am on.

more than half of the counties in the US are low on water). There was even music: drum songs opened the first Indigenous session, and the DJs at the SolarSoundSystem (run by the “muscle power” of conference attendees on bicycles instead of its touted photovoltaics, since we weren’t out in the sunshine) spun an international mashup everyday from 11:00am on.

But this was, after all, a UN affair, and it was well organized and convivial. Though perhaps a bit too convivial. The Indigenous Peoples’ Pavilion was one of the first I searched out. It sat adjacent to the International Energy Agency (IEA). I asked a few people working the corner stand at the Indigenous pavilion if they knew about the IEA. They did not, and suggested I ask the well-dressed gentleman at the IEA counter (there was no agenda here—they were simply being helpful). I knew of the IEA, but I stopped by their counter later out of curiosity to hear their current pitch. I wasn’t surprised to discover that the Agency was now touting itself as an environmental advocate.

The IEA was established in 1974 to address major disruptions in the supply of oil as a response to 1973 oil crisis. Despite movements to broaden its interest in renewables the IEA continues to be heavily criticized by environmental organizations for consistently being overoptimistic about oil and under optimistic about the amount of energy that can be produced by wind power and other alternative energy sources.

Unlike the space set asi de for the IEA, which seemed like a ghost town every time I passed by (hopefully a positive indication?), the roughly 25 foot square presentation room of the Indigenous Peoples’ Pavilion was always packed with interested listeners. Dozens overflowed outside the two doorless entranceways, jostling to listen and get a better view of the presenters from the world’s historically embargoed inhabitants. [see photo 2]

de for the IEA, which seemed like a ghost town every time I passed by (hopefully a positive indication?), the roughly 25 foot square presentation room of the Indigenous Peoples’ Pavilion was always packed with interested listeners. Dozens overflowed outside the two doorless entranceways, jostling to listen and get a better view of the presenters from the world’s historically embargoed inhabitants. [see photo 2]

The lack of a deep historical awareness was distressing (a survey of all the official sessions revealed no direct reference to history—COP21 was up-to-date and all about the present and future). History is one of the indispensable avenues for opening the important complexities of representation and narrative. Narratives, for instance, are essential to the study of not only history, but also literature, art, philosophy, and other human sciences. Studying how narratives lead to the creation of ideas and beliefs, and how these in turn generate physical structures of existence are central concerns of my work as a humanist. Narratives are the raw material in the humanist lab, and examining the precise manner in which certain narratives are historically given more political power than others reveals the how and why of human (and ecological) history. Such concerns can open a substantive consideration of the ideological root causes of climate change.

Environmentalists have been battling governments, conservative denial, corporate environmental abuse, and environmental injustice for decades. This sense of struggle and inequality was generally occluded by the judiciousness of the COP planners.

Even the city of Paris was shockingly quiet. No doubt a great deal of this calmness was the result of the attacks that occurred two weeks before the start of the summit. Environmental activist groups had planned protests throughout COP21, but the city was still under a state of emergency, and demonstrations were banned. The day before the conference 200 protesters fought with police around the Place de la Republique square. 174 were jailed and others were kept under house arrest. My hotel was situated just off the square, and I walked past dozens of police in riot gear each morning on my way to catch the metro to Le Bourget.

Even the city of Paris was shockingly quiet. No doubt a great deal of this calmness was the result of the attacks that occurred two weeks before the start of the summit. Environmental activist groups had planned protests throughout COP21, but the city was still under a state of emergency, and demonstrations were banned. The day before the conference 200 protesters fought with police around the Place de la Republique square. 174 were jailed and others were kept under house arrest. My hotel was situated just off the square, and I walked past dozens of police in riot gear each morning on my way to catch the metro to Le Bourget.

However, there were other, less sanctioned events that brought the question of history, narrative, and inequality into the mix. Public demonstrations of criticism may have been banned, but not from the airwaves. Radio Campus France—a network of 29 FM stations across the nation—launched “GOOD COP BAD COP21.” [see photo 8]A 24/7 live radio and web broadcast of news, editorials, interviews, debates, information, and music, GOOD COP BAD COP21 was heavily critical of past and present international response to climate change. Broadcasts ran for the length of the conference. The team held interviews and deliberated with scientists, philosophers, activists, and journalists, and worked with activist climate organizations like Alternatiba (one of the main forces involved in the demonstrations denouncing the agreement at the end of COP21). During the first week they held live broadcasts throughout Paris, “flea-jumping” from the Glass Theater to a recycling plant, to Le Bourget, interviewing members of the public but also representatives from organizations like 350.org and noted intellectuals like the French anthropologist and philosopher Bruno Latour.

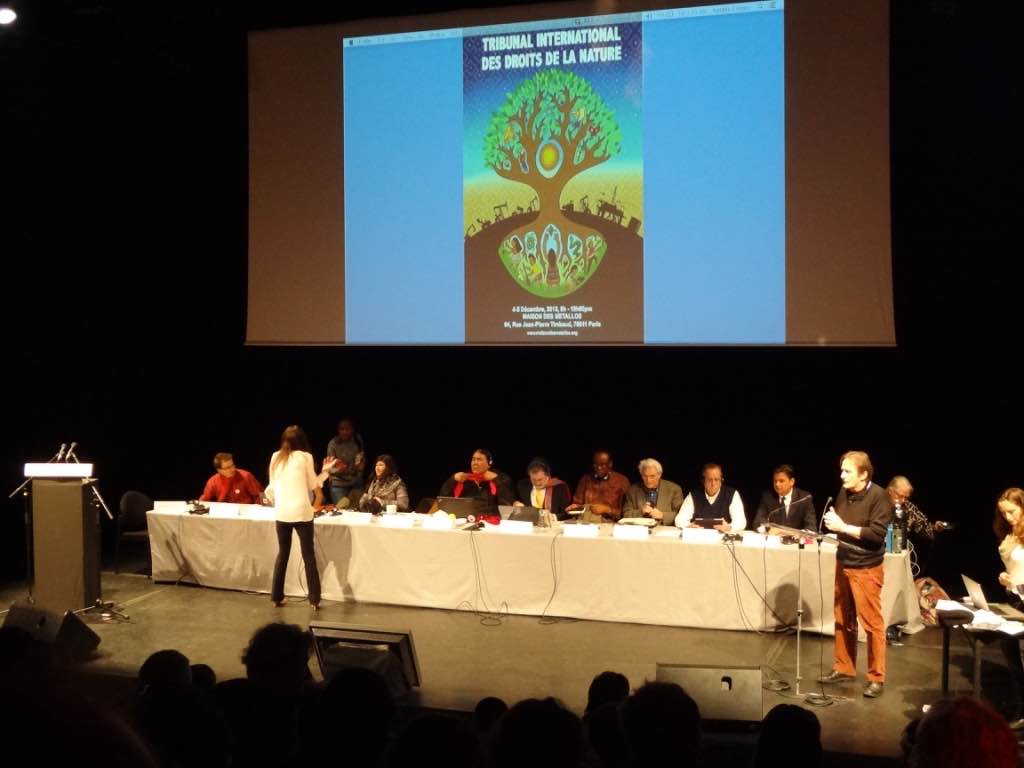

By far the most powerful off-site event was the International Rights of Nature Tribunal. [see photos 9 and 10] The inspiration for the Tribunal came from the International War Crimes Tribunal, but unlike its more famous predecessor, the Rights of Nature Tribunal extends beyond human-centered rights to recognize “all natural entities,” including “plants, animals, rivers and ecosystems.” The UN climate change accord mentions the economy and economics 26 times, yet it only mentions the Earth once, and nature not at all. The Tribunal was a reparation for symptomatic neglect. Comprised of international lawyers and leaders of planetary justice, the Tribunal operates as a counter-narrative to existing international law (it emphatically denies, for instance, state sovereignty over natural resources). It offers a “systematic alternative to environmental protection, acknowledging that ecosystems have the right to exist, maintain and regenerate their vital cycles.”

By far the most powerful off-site event was the International Rights of Nature Tribunal. [see photos 9 and 10] The inspiration for the Tribunal came from the International War Crimes Tribunal, but unlike its more famous predecessor, the Rights of Nature Tribunal extends beyond human-centered rights to recognize “all natural entities,” including “plants, animals, rivers and ecosystems.” The UN climate change accord mentions the economy and economics 26 times, yet it only mentions the Earth once, and nature not at all. The Tribunal was a reparation for symptomatic neglect. Comprised of international lawyers and leaders of planetary justice, the Tribunal operates as a counter-narrative to existing international law (it emphatically denies, for instance, state sovereignty over natural resources). It offers a “systematic alternative to environmental protection, acknowledging that ecosystems have the right to exist, maintain and regenerate their vital cycles.”

We’re told often in the face of resistance to new knowledge that “the science will out.” Perhaps, in the wake of COP21, nature will out. It certainly did at the Place du Pantheon in the 5th arrondissement on December 5, 2015—the day a dozen calves of ice appeared from the Greenland ice sheet. [see photos 11, 12, and 13] “Ice Watch” was the creation of Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, who caught the pieces floating in the Davis Strait.

T he Pantheon in the Latin Quarter is the original site of Foucault’s pendulum—proof of the Earth’s rotation. These shrinking monoliths of the North Pole were proof of Earth’s global warming.

he Pantheon in the Latin Quarter is the original site of Foucault’s pendulum—proof of the Earth’s rotation. These shrinking monoliths of the North Pole were proof of Earth’s global warming.

The fragments of ice were arranged in a circle like a clock, to reflect the passage of time. Their spectral presence sounded the death of a landscape brought about by our indifference. Boulder-sized, they were ghostly. I imagined they had walked here from the North Pole, to look for someone in charge—the planet’s most marginalized identity, seeking representation at the cost of life. They were metaphors ridiculing the resource management of our unsustainable lifestyles, mute witnesses on a hunger strike that would not end well. They were not alive according to human understanding, yet they exhaled air from snow that fell thousands of years ago. The air they were giving us was the purest on the planet. Will we be able repay that gift in kind?

[1] Specifically, the accord aims to keep temperatures “well below” 2 degrees and “endeavors to limit” temperatures to 1.5 degrees.