There's no shame in 'Learning to Read'

‘Aprendiendo a Leer’ program teaches Latino elementary school students to be proud that they speak multiple languages

Seated at a table in the Wea Ridge Elementary School resource center with three fellow fourth graders and Purdue student volunteer Nathan Macatangay, Carol Munoz excitedly described the afterschool program she attends every Wednesday.

“This is one of my favorite classes out of all the years I’ve been to it,” she said, noting that she has participated in the Aprendiendo a Leer program since before she started kindergarten.

If you’re bilingual like Carol, you already know that Aprendiendo a Leer means “learning to read” in Spanish. And like Carol and her classmates, you are probably aware that learning how to read, write, and speak more than one language can be extremely useful for any number of reasons.

“Later on in the future you might need it,” said her classmate, Kevin Sanchez.

“What if I want to become a Spanish teacher?” Carol asked, before classmate Octavio Berumen chimed in that he, too, might like to become a teacher someday.

Had Alejandro Cuza, Director of Linguistics and Professor of Spanish and Linguistics at Purdue, and the other leaders of the Aprendiendo a Leer program been seated around the table, the children’s comments would have been music to their ears.

At its most basic level, the biliteracy program is designed to help Latino children maintain their Spanish-speaking ability so that they may communicate with family members and develop the skills to read and write in the language they may have only learned how to speak at home. But that is not the program’s only objective.

“Even though the main intention of this program is to teach these children to read and write in their native language, for us personally here locally, one of our biggest goals is to expose these children to the importance of seeing their bilingualism as an asset rather than something to be ashamed of,” said Esmerelda Cruz, a health and human sciences educator with Purdue Extension who facilitates the program for children from three elementary schools in Frankfort.

A matter of cultural identity

Some students don’t enter the Aprendiendo a Leer program with that perspective. When children want to fit in with their classmates, it’s easy for them to see being different as a weakness. And when they sometimes start school without an ability to speak English like their fellow students, the language barrier can cause them to withdraw.

“In school, I couldn’t really communicate with my teacher and my friends,” Sanchez said of his earliest days in elementary school. “I was just really quiet.”

Kevin’s experience is perfectly normal, Cruz said. The students sharpen their English skills alongside the other members of their traditional classes during the school day, but rarely would they receive instruction to develop basic language skills in Spanish. That’s where Aprendiendo a Leer comes in, teaching them about vocabulary, spelling, and sentence structure after school as they learn to appreciate the positive sides of their bilingualism.

“One of the boys in our program still struggles with being Latino, based on our interactions, and what he shares, and his attitude in the classroom,” Cruz said. “But for most of our kids, we see this change from the fall semester to the spring semester as to the appreciation and the value they place on their ability to speak two languages.”

In fact, Cuza cited research indicating that bilingualism can improve the speaker’s abilities in each individual language – a reality that contradicts a common educational instruction where teachers encourage Latino parents to speak English to their children at home.

“Some people thought, and unfortunately still think, that it was the opposite – that teaching Spanish-background children their heritage language prevents them from learning English and discourages them from ‘assimilating’ to mainstream society,” said Cuza, who established the program in 2011.

Addressing the problem

Cuza designed Aprendiendo a Leer to help alleviate the problems this language conundrum can create for the families, most of whom emigrated from Mexico.

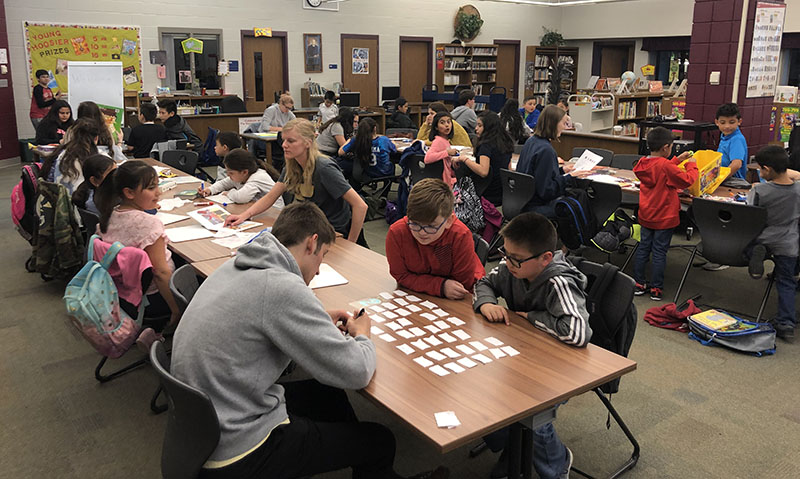

For 16 weeks in the fall and spring semesters, the student volunteers from Purdue work with children at Wea Ridge under the guidance of program coordinator Nancy Reyes. And in Frankfort, Cruz leads a team of instructors that includes moms who are former teachers themselves. One afternoon per week, they lead the children through reading exercises, learning activities, games, and occasionally sing songs. Everyone is encouraged to speak Spanish throughout.

In many cases, the language-acquisition lessons benefit the teachers and volunteers, as well.

“I would like to be a pediatric pharmacist one day, so there’s definitely down-the-road value to this because I get to interact with children,” said third-year pharmacy student Macatangay, who is in his third semester working with Carol, Kevin, Octavio, and Esmerelda Medrano’s group. “I have shadowed pediatric pharmacists who worked with children a lot. When they have parents, especially, who speak Spanish, it’s difficult to make sure everything works out well.

“So I feel like I would be able to interact better with Spanish-speaking parents, and then a lot of times if the children also don’t speak English so well, hopefully I’ll be able to interact with them. Hopefully this can help me get better at that, because I feel I’ve already gotten better at understanding them.”

The Purdue student volunteers at Wea Ridge are typically Spanish majors or minors taking advanced Spanish courses at the 300 level, where they receive extra credit for committing to help with the program. But like Macatangay, some volunteers return to help even after they stop receiving class credit – one of the many rewarding aspects of the program for Reyes.

“Every semester I have some who ask to come back,” said Reyes, a doctoral student studying bilingualism and language acquisition. “If they were good one semester, I’m glad to have them back because I don’t have to retrain them and they know the children. If they want to come back, there’s a reason. They enjoy it, so they give a positive contribution.”

Through funding assistance from service learning grants, the Kinley Trust Foundation, Purdue’s College of Liberal Arts, and the Office of Engagement, the program has been active for nearly a decade, teaching children that their bilingualism makes them special.

Learning to appreciate that uniqueness often makes all the difference in their academic – and personal – growth.

“When you have a negative attitude toward something, you’re going to be closed off. You’re not going to want to engage with it and you’re not proud of it,” Cruz said. “But when you see it as an asset and something you’re proud of, it’s not just about that one thing, it’s about your person as a whole, I think, that also is influenced.”