The Purdue OWL turns 25

How Purdue created the world's first Online Writing Lab

Did you know that the Purdue website that attracts the most traffic is not purdue.edu, nor is it the site for Purdue sports? Nope, it’s the Purdue Online Writing Lab, which started 25 years ago as a delivery device for the Purdue University Writing Lab’s wealth of resource documents and instructional material.

“The coolest thing about it is it started in a filing cabinet,” said former OWL webmaster Jeffrey Bacha, now an associate professor of English at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

That it did. It developed a following shortly after Writing Lab director Mickey Harris and her students digitized the writing handouts stored in that filing cabinet, initially making them available for free via email. Before long, the OWL’s reach stretched across the globe.

“It’s almost like a cultural phenomenon because every person who goes to college, in the United States at least, takes first-year writing, and almost all of those instructors use the OWL in some way. That’s just how it is,” said former OWL webmaster Dana Driscoll, an associate professor of English at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. “Then you have all of the advanced courses. Then you have the graduate students.

“So suddenly, almost anyone who’s doing something in higher education in English is probably encountering the Purdue OWL in some way. That’s like billions of people. If you think about it, it’s kind of insane.”

Driscoll’s guestimate was not too far off base. In 2017-18, the OWL surpassed 500 million annual pageviews and drew more than a million clicks from 14 different countries. Webmaster Tony Bushner believes that the site could reach a billion annual clicks by the early 2020s.

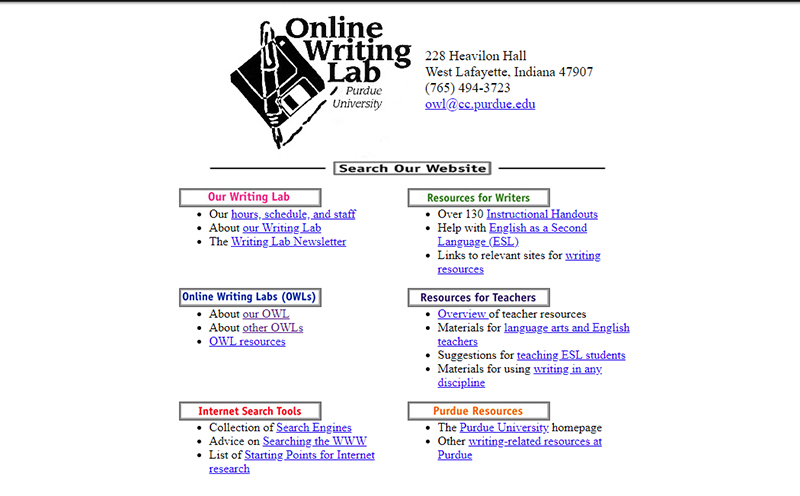

First Steps

Like many great success stories, the OWL’s expansion beyond that Heavilon Hall filing cabinet came about as a result of hard work and ingenuity.In the early 1990s, Writing Lab founder Harris wanted to find a way to make the documents – covering subjects like comma usage, proofreading strategies, the differences between quoting and paraphrasing, and recommendations on how to avoid sexist language in writing – available to students 24/7, not just during the weekday hours that the Writing Lab was open.

Student Michael Manley developed the initial infrastructure that allowed students to access the documents they wanted via email.

“They got a huge chunk of our handouts online,” Harris recalled. “We had an index, and if students looked through the index, they picked the number of the handout they wanted. Usually it was on a Sunday night when they were writing their papers and we were closed. They could request a handout and it instantly came back to them.”

The email service gained a global audience almost immediately, but the biggest step was still to come. Demand for the OWL’s services exploded shortly after Harris’ collaboration with a graduate student named Dave Taylor.

“He came into the Writing Lab and said, ‘Do you know about the web?’ And I said, ‘Not really,’ ” Harris said. “This was in the early stages of the web, when the first browser was called Mosaic. He introduced me to Mosaic and I thought, ‘That’s incredible.’ He said we could get all the handouts up on this website and it could be available to anybody at any time.”

And so the OWL was born. Taylor soon redesigned the email server and created the first incarnation of the OWL website – generally accepted as the world’s first online writing lab – and Stuart Blythe helped get the site onto the internet.

A student in educational computing, Taylor actually wrote a thesis about making the OWL available on multiple interactive channels and surveying users to discover which channels they found most satisfying.

“It progressed pretty quickly,” Taylor said. “I remember they did a feature on the website in one of the big Chicago papers and I remember feeling this huge success: ‘For my thesis to be of any value, I need a lot of traffic, and now we’re going to get a lot of traffic. This is going to be awesome.’ We were definitely aware, even as I was developing it, that it was going to be one of the first really meaningful, incredible academic resources on the World Wide Web.”

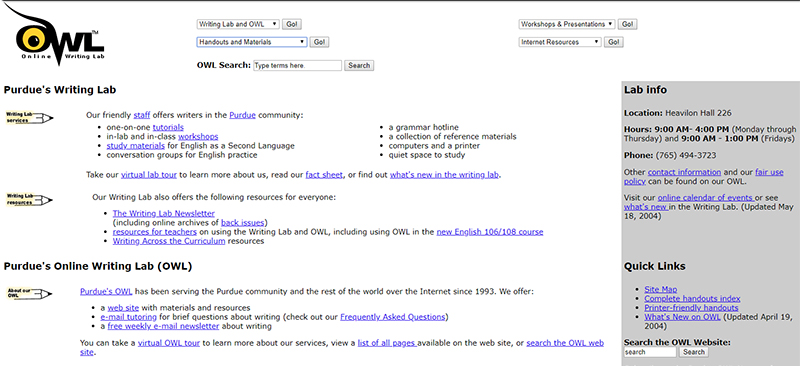

Global Expansion

Taylor’s instincts were correct. Although the site received a somewhat lukewarm reception at Purdue, it quickly attracted attention abroad. Within the first few years, the site attracted millions of total hits per year and users from approximately 100 countries.Ask anyone who has served as an OWL administrator about their interactions with international users and nearly all of them will have an incredible story at the ready. Harris alone could fill a book with her recollections.

She remembered hearing that workers at a research station in Antarctica used the site to help them write reports. She also told of receiving a thank-you note from a man who landed a job with a company in India after using the OWL to format his résumé in English.

“I have a friend who was at the American embassy in Russia a couple of years ago and introduced herself as being from Purdue,” said Margaret Rowe, head of the English department when the OWL first launched and later dean of the School of Liberal Arts. “The first thing the person mentioned to her was OWL. He had just used it.”

Former OWL coordinator Allen Brizee told one of the most memorable versions of these stories.

“I got messages from people in Northern Iraq, right after the Iraq war, who were teaching the teachers of English for the Kurds,” recalled Brizee, associate professor of writing at Loyola University Maryland. “They said they didn’t have money for textbooks, but they had money for a computer, a satellite uplink, and a printer. They said, ‘We are teaching the Kurdish teachers to teach students how to read and write in English with the Purdue OWL.’ ”

Driving Forces

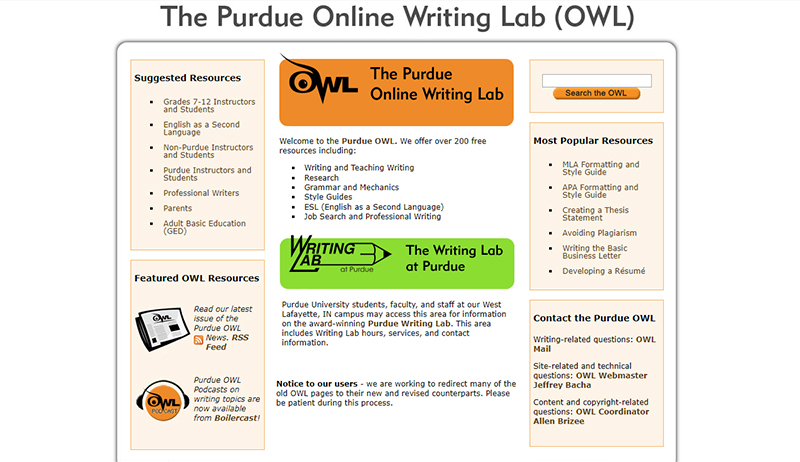

The many former graduate students who served as OWL content creators through the years are responsible for the incredible depth of material that is available on the site today.Yes, the site’s citation pages explaining the rules of APA and MLA style still draw the bulk of OWL web traffic, but the site also features helpful resources addressing just about any subject where a writer might need assistance. There are teaching resources, pages devoted to résumés and cover letters, a section for writers using English as a second language, and a YouTube page featuring helpful writing instruction that boasts nearly 22,000 subscribers. There is even a microsite dedicated to the many community engagement projects coordinated by OWL representatives through the years.

“What I’m most proud of, inheriting this great tradition of the Writing Lab and the OWL, is everything you see on those pages is a culmination of a history of students doing most of the work and faculty supervising, advising, coaching,” said Harry Denny, director of the Writing Lab and OWL. “But that’s all a collection of student work, whether it’s undergrad or mostly graduate students. I think that’s a testament to teaching and learning at Purdue. We have a great culture for that.”

The culture Denny inherited when he joined the Purdue faculty in 2015 was the direct result of work done by Writing Lab predecessors like Linda Bergmann, Tammy Conard-Salvo, and perhaps most of all, Harris.

“Mickey is one-of-a-kind. She really is a visionary,” Rowe said. “When she started with OWL, I was able to give her a little bit of support, and I think some other people did, but Mickey made miracles happen despite administrators. She never got the kind of support from anybody that she should have in getting things off the ground because she was running rings around us in terms of what she could see and what she was willing to work toward.”

Still Growing

Each year that the OWL exists, student contributors write and film new content that adds wrinkles to the site’s ever-expanding wealth of resources. These contributions, on top of the citation pages that attract the greatest portion of web traffic, help the OWL maintain its foothold as one of the world’s most prominent online writing resources.“Nowadays, I think that every university has its own resources online that are available to anyone,” said former OWL webmaster Fernando Sanchez, assistant professor of English at the University of St. Thomas. “However, the longevity of the OWL has allowed it to branch out and create content not only for citation questions, but for numerous writing situations as well.

“I remember the very first project I did for the OWL was a piece on how to write a college application. It’s like a snowball effect, I think. We’ve already had these resources for so long (which we continue to update), that we can allow our attention to focus on other writing needs. Other online resources (not from the OWL) are only getting off the ground by comparison.”

Looking toward the future, Denny envisions an OWL that continues to expand its multimedia resources and interactivity, focusing more on writing across disciplines and on engaging with multilingual writers.

The OWL’s end goal will remain unchanged, however. The site first stretched beyond Heavilon Hall by doing its part to fulfill Purdue’s land-grant mission, aiding local, national, and international writers who needed assistance. No matter how the site changes in the future, that is what the OWL will continue to do.

“Purdue did a great job of doing something that I think every college has with a little writing help center and we just made it a bigger thing and a more successful thing that was a greater resource for a larger number of people,” Taylor said. “And that’s a great story.”